Pleurisy

Pleural Effusion

Pneumothorax

Chylothorax

Mesothelioma

References

Further reading

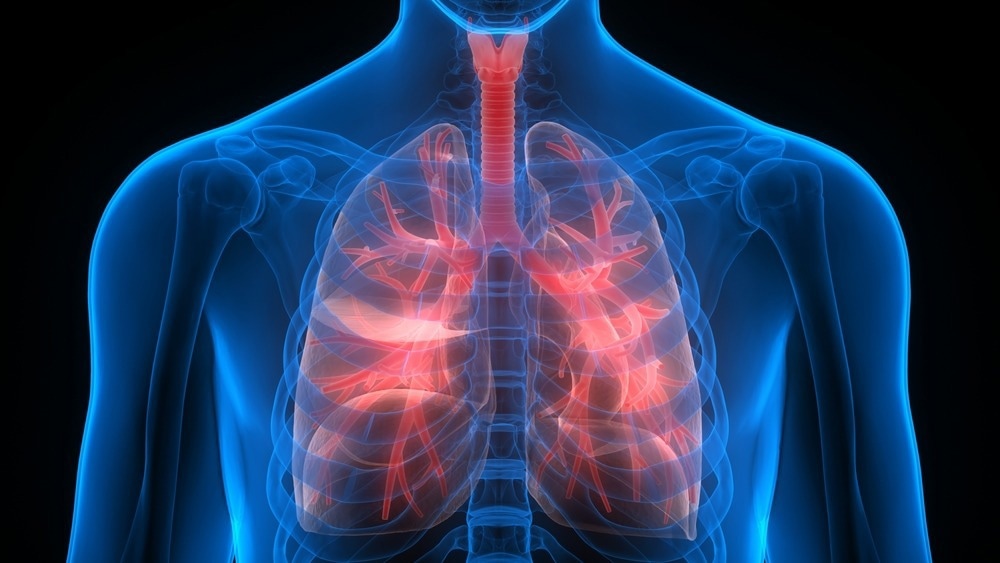

Pleural diseases affect the pleural tissue that lines the inside of the chest cavity and covers the outside of the lungs. The visceral pleura (which covers the lung) and the parietal pleura (which covers the chest wall, diaphragm, and mediastinum) constitute the pleural space.

Image Credit: Magic mine/Shutterstock.com

Pleurisy, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax are the three primary pleural diseases. Common symptoms include chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, and coughing. With an incidence of 360 cases per 100,000 individuals, the cases are expected to increase globally.

Pleurisy

Pleurisy is a sign of a disease-causing inflammation of the pleura that causes localized chest pain and may occur due to a primary pleural disease or a subsequent sickness.

In 1961, Giambattista Morgagni defined "pleurisy" as a sickness of the pleura and "peripneumony" as a disease of the lung tissue. It can develop as a sharp pain in the thoracic or shoulder, accompanied by coughing and sneezing.

Travel history, alcohol use history, tobacco/electronic cigarette use, and illicit (intravenous) drug use history may indicate the underlying cause of pleurisy.

Pleurisy can develop quickly (in minutes to hours) in acute coronary syndromes, pulmonary emboli, acute pericarditis, and chest wall injuries. Tachypnea and dyspnea are common in acute and hyperacute pleurisy.

Synpneumonic pleurisy caused by viral and bacterial pneumonia can develop over hours to days. Subacute or chronic (days to weeks) pleurisy is commonly associated with rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, or tuberculosis.

Pleural Effusion

A pleural effusion is an abnormal buildup of fluid in the pleural space. Pleural effusions are associated with various lung, pleural, and systemic illnesses. Congestive heart failure, cancer, pneumonia, and pulmonary embolism are the most common causes.

Drugs like beta-blockers, clozapine, dantrolene, and nitrofurantoin, among others, may also cause pleural effusion. The volume of the fluid present and the underlying etiology determine the clinical manifestation of pleural effusion.

Many people may have no symptoms when they are diagnosed. Pleuritic chest discomfort, dyspnea, and a dry, ineffective cough are all possible symptoms.

Image Credit: Vladimir Sukhachev/Shutterstock.com

The most common cause of the malignant pleural effusion is lung cancer, followed by breast cancer. Pleurodesis, thoracoscopy, video-assisted thoracoscopy, and the implantation of a permanently indwelling pleural catheter are all options for treating pleural effusion in addition to the therapy of the underlying disease.

Pneumothorax

In pulmonary medicine, whether spontaneous or trauma-induced, pneumothorax is commonly diagnosed. Dyspnea and chest pain from the lung and chest wall are characteristics of a pneumothorax.

Pneumothorax can only occur if the air is allowed to enter due to damage to the lung or chest wall or sporadically because of gas production by bacteria in the pleural space. Primary pneumothorax and secondary pneumothorax are other categories of spontaneous pneumothorax.

When a pneumothorax develops without obvious etiology and substantial lung disease, it is called primary pneumothorax. On the other hand, secondary pneumothorax happens when there is already lung disease present.

Smoking is one of the main risk factors for primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP), which frequently affects young male adults. Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax (SSP) occurs in people with a pulmonary disease diagnosis.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), sometimes called chronic bronchitis or pulmonary emphysema, is the most prevalent related cause.

Traumatic pneumothorax occurs when the chest wall is punctured as air enters the pleural space after a stabbing or gunshot wound. Only rib fractures are more frequent in this subset of chest trauma cases, where traumatic pneumothoraces have been observed to occur in up to half of all cases.

Image Credit: Chinnapong/Shutterstock.com

Moreover, individuals already getting mechanical ventilation for another reason have also experienced this pneumothorax. Depending on various variables, pneumothorax treatment can range from rapid needle decompression or chest tube implantation through discharge with prompt follow-up.

Chylothorax

Chylothorax results when a lymphatic fluid (chyle) builds up in the pleural cavity due to lymphatic channel leakage. In 0.5% to 1% of instances, it is most frequently observed following thoracic surgery and in conjunction with malignancies.

Chylothorax can result from various disorders that might clog the thoracic duct or produce abnormal lymphatic flow, including congenital, viral, neoplastic, and many more. Today, there are many different ways to treat chylothorax, from conservative measures to surgical and, more recently, interventional radiological techniques.

The most frequent cause of traumatic chylothorax is a surgical complication following a thoracic operation or treatment, which can be blunt or penetrating. Leaks in the lymphatic channels are brought on by direct infiltration or restricted flow brought on by compression and buildup in non-traumatic chylothorax.

Lymphopenia (absolute circulating peripheral lymphocyte count of less than 1500/l), which is closely correlated with a prolonged chylous leak duration, is one of the long-term consequences. Children with hematological chylothorax problems have also been documented. Possible causes of congenital chylothorax in one in 20,000 pregnancies include birth trauma or lymph vessel abnormality. Children typically experience chylothorax less frequently.

Chylothorax is identified and distinguished from other types of effusion based on a laboratory chemical analysis of the pleural fluid aspirate.

The presence of chylomicrons is a distinguishing feature. Appropriate nutrition, electrolyte replacement, and fluid replacement are the cornerstones of treatment.

Young patients with a high-volume chyle leak should undergo surgery as soon as possible. Several radiological procedures can be applied to traumatic and non-traumatic chylothorax.

Mesothelioma

Most patients of mesothelioma are older adults who have worked around asbestos. The incidence and fatality rates of mesothelioma worldwide remain unknown. After the extensive usage of asbestos during World War II, there was a significant rise in the age-standardized mesothelioma incidence and fatality rates that started in the 1960s.

In Australia, the United States, and Western Europe, where asbestos was outlawed or closely controlled in the 1970s and 1980s, mesothelioma incidence rates have declined.

Pleural mesothelioma patients commonly experience dyspnea, accompanied by a dry cough, fatigue, chest pain, and weight loss. In about 12% of individuals, pathogenic germline mutations in BAP1 and, less commonly, other tumor suppressor genes have been found.

This subset of genetically related mesotheliomas (M: F ratio of 1:1) with a survival time of five to 10 years or longer affects younger people who infrequently disclose asbestos exposure. Identifying people who inherited the mutations will benefit from early detection screening by genetic testing of relatives.

The primary imaging technique is a CT scan of the upper abdomen and chest. Improved prevention, early identification, and treatment will require multidisciplinary, international collaboration.

Randomized trials have been published in facilities with significant clinical and research pleural services during the past few years. Also, studies to better understand the pharmacodynamics of medications in the pleural space, trials examining the clinical impact of pleural manometry, and an investigation into the relationship between pleural disease may be forthcoming.

Investigations of the genetic composition of affected people and patient-centered outcomes are also being done. Pleural disease is still a frequent clinical issue, and patients can receive the best care possible with interdisciplinary examination and treatment.

References

- What Are Pleural Disorders? (2022). [Online] NIH. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/pleural-disorders#:~:text=There%20are%20three%20types%20of,is%20inflammation%20of%20the%20pleura.

- Bodtger, U., & Hallifax, R. J. (2020). Epidemiology: why is pleural disease becoming more common. European respiratory Society monograph: pleural disease. Sheffield: ERS, 1-12.

- Hunter, M. P., & Regunath, H. (2020). Pleurisy. PMID: 32644384

- Jany, B., & Welte, T. (2019). Pleural Effusion in Adults-Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Deutsches Arzteblatt international, 116(21), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2019.0377

- Carbone, M., Adusumilli, P. S., Alexander, H. R., Jr, Baas, P., Bardelli, F., Bononi, A., Bueno, R., Felley-Bosco, E., Galateau-Salle, F., Jablons, D., Mansfield, A. S., Minaai, M., de Perrot, M., Pesavento, P., Rusch, V., Severson, D. T., Taioli, E., Tsao, A., Woodard, G., Yang, H., … Pass, H. I. (2019). Mesothelioma: Scientific clues for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 69(5), 402–429. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21572

- Feller-Kopman, D., & Light, R. (2018). Pleural disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(8), 740-751.

- Bender, B., Murthy, V., & Chamberlain, R. S. (2016). The changing management of chylothorax in the modern era. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery, 49(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezv041

- Choi, W. I. (2014). Pneumothorax. Tuberculosis and respiratory diseases, 76(3), 99-104.

- Zarogoulidis, P., Kioumis, I., Pitsiou, G., Porpodis, K., Lampaki, S., Papaiwannou, A., Katsikogiannis, N., Zaric, B., Branislav, P., Secen, N., Dryllis, G., Machairiotis, N., Rapti, A., & Zarogoulidis, K. (2014). Pneumothorax: from definition to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of thoracic disease, 6(Suppl 4), S372–S376. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.09.24

- Schild, H. H., Strassburg, C. P., Welz, A., & Kalff, J. (2013). Treatment options in patients with chylothorax. Deutsches Arzteblatt international, 110(48), 819–826. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2013.0819

- Karkhanis, V. S., & Joshi, J. M. (2012). Pleural effusion: diagnosis, treatment, and management. Open access emergency medicine : OAEM, 4, 31–52. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAEM.S29942

- Pleural Disorders. [Online]. Tampa General Hospital. Available at: https://www.tgh.org/institutes-and-services/conditions/pleural-disorders

Last Updated: Apr 21, 2023

Source: Read Full Article