Nearly $200 million is being added to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) COVID-19 tracking efforts to find new strains of the virus. The White House announcement will expand sequencing to about 25,000 positive coronavirus tests weekly, triple the current level.

Until now, the United States has sequenced genomes from about 1% of positive COVID-19 test samples. And it is a trio of SARS-CoV-2 variants that have dominated the pandemic landscape so far.

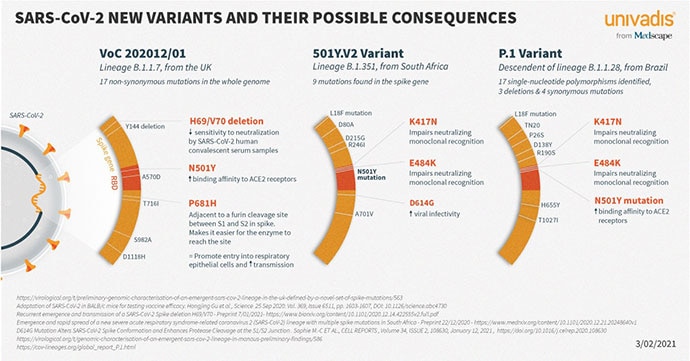

The three variants — B.1.1.7., discovered in the United Kingdom; B.1.351, from South Africa; and P.1., originating in Brazil — all share spike protein mutations called N501Y and E484K. Both appear to help bind the spike protein to human ACE-2 receptors, making the virus easier to catch.

Duncan MacCannell, PhD, head of the CDC’s SPHERES consortium, a national genomics partnership coordinating SARS-CoV-2 sequencing, said he’s trying to get a much better picture of what’s happening across the country.

|

|

|

|

The purpose of sequencing is to see trends, he said. “To paint with broad strokes what’s circulating in the country.”

With Florida a hotspot of sorts for B.1.1.7., accounting for about a quarter of the nation’s more than 2500 documented cases of COVID-19 linked to that variant, experts suggest that a relaxation of public health measures, such as masking, is linked to the strong emergence of that variant in the region, as it was for the original strain.

As of March 2, Texas, which is lifting mask mandates and ending COVID restrictions, has 101 cases of B.1.1.7.

In New York, preliminary sequencing efforts have identified another new variant: B.1.526. It first appeared in samples collected in November, and by mid-February, it accounted for about one in four sequences in the database shared by scientists.

Looking Ahead

Sequencers warn that the coming months will be a race between getting vaccines in arms and the virus’s ability to mutate.

Lea Starita, PhD, a research assistant professor of genome sciences at University of Washington in Seattle, said she’s concerned that these two major factors will intersect to cause big problems in the next 6 months to a year.

“I’m worried about the convergence of the vaccines and high transmission rates,” she said. “The transmission rate, while decreasing, is still higher than it should be. Having some decent percentage of the population vaccinated, plus high transmission, could give the virus a lot of chances to evade vaccine immunity.”

Crucially, sequencing efforts over the coming months must include positive COVID-19 test samples from patients who have already been vaccinated. “Breakthrough infections need to be sequenced at a high rate,” Starita said. “This will help us see the worrisome things early.”

The CDC is monitoring other variants “defined not by specific lineages, but patterns of mutations they take,” MacCannell said. They are watching a cluster of seven unique variants newly revealed in the United States that share a mutation in a single letter of the spike amino acid chain. Although this common mutation in amino acid position 677 certainly makes the cluster a curiosity, it’s still not known whether it also makes the variants more contagious.

“What these mutations mean, we don’t fully understand yet,” MacCannell explained. “It’s very likely they have some impact on the success of the virus and are certainly worth monitoring. We will be watching fairly closely as well because it’s clearly something that’s conferring some sort of evolutionary advantage to the virus.”

The Mutating Virus

The convergence of the 677 mutation in each of them suggests something is happening to give it an advantage, said Jeremy Kamil, PhD, who coauthored the preprint detailing the seven variants.

“It makes them possibly more contagious than the ancestral strain,” said Kamil, a virologist at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport. But, he added, “all we have now is a potential evolutionary signal. We have not found a more transmissible variant; we’ve found evidence it’s worth looking into.”

Indeed, a convergence of mutations is anticipated as the virus continues to spread and evolve. “It’s not unusual, when you roll the dice millions of times, that you come up with the same number,” MacCannell pointed out. “And as the virus replicates, even in an individual person, it’s like the roll of the dice.”

Mary Hayden, MD, is coprincipal investigator of a new molecular laboratory at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago that will track emerging coronavirus strains, including the seven recently identified in the United States, which she calls “variants of concern.”

Hayden speculates that B.1.1.7 will become the dominant strain around the globe. And it “seems to be as susceptible to natural immunity that arose from infection as the original variant,” she said, “so it seems the vaccines we have now should be fine.”

Vaccine Implications

Current data suggest that vaccines approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are effective protection from strains circulating in the United States, the agency reported last week. But vaccines might need to be tailored to any variants that become resistant, and there is some debate about whether booster shots will eventually be needed.

Pandemic fatigue creates more of a “real risk” from the concerning SARS-CoV-2 variants already in circulation, said Lane Warmbrod, MS, MPH, a senior analyst at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore.

Warmbrod coauthored a report released February 16 on how policy and public health measures can stay ahead of variants, which recommends priorities, including continuing public health measures such as mask mandates and limited gatherings.

“In public health, we spend a lot of time looking at human behavior. We know that the general population, if they’ve been following these public health measures to begin with, are very tired now,” Warmbrod acknowledged. “Most of the response, from a practical level, is trying to get people to follow the rules already out there. It’s just a hard balance.”

Boosters might not be necessary if people are vigilant. “If it’s B.1.1.7. that takes over and becomes the dominant lineage in the United States,” as is expected, Warmbrod said, “I think we have a strong chance it won’t be critical that we need a booster.”

Starita, however, said boosters will “absolutely” be necessary. Although “no one who’s gotten the vaccines already produced has died of coronavirus,” she added, “to stop symptomatic infection going forward, there will need to be boosters.”

But they “might not be needed every year,” Starita pointed out. Coronavirus doesn’t have as many tricks up its sleeve as flu does. Maybe we’ll need one every 5 years, or every 3.”

MacCannell said he also “would not be surprised” if vaccine composition was tweaked over time in response to variants or if boosters were necessary.

“That’s another reason why large-scale genomic surveillance is important,” he explained. “It helps us monitor changes in circulating virus and assess the efficacy of vaccines to help us decide early where there need to be changes.”

Follow Medscape on Twitter @Medscape and Maureen Salamon @maureensalamon

Source: Read Full Article