With numerous studies documenting air pollution’s link to heart-related illness and death, two leading American physicians are calling on their peers to begin screening patients for exposure to indoor and outdoor air pollution and recommending interventions in order to limit exposure and improve cardiovascular health, the researchers write in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In addition, governments have a primary responsibility, as stewards of public health, to adopt technologies and regulations that reduce air pollution—measures that will also contribute to efforts to combat climate change, write Philip J. Landrigan, MD, director of the Global Public Health and the Common Good Program at Boston College, and Sanjay Rajagopalan, MD, chief of cardiovascular medicine at UH Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute, the Herman K. Hellerstein, MD, Chair in Cardiovascular Research, and director of the Case Cardiovascular Research Institute at the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine.

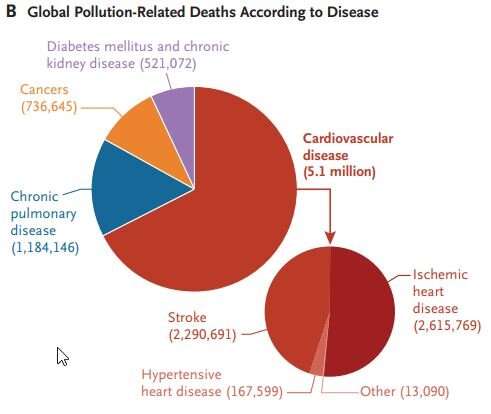

Cardiovascular diseases are the world’s leading cause of death and disability, responsible for 18.6 million deaths worldwide in 2019, including 957,000 deaths in the United States. That same year, an estimated 5.5 million cardiovascular deaths were linked to air pollution—including 200,000 deaths in the United States, though the authors note that number could be up to ten times higher, based on a number of studies.

The grim statistics illustrate that it is now necessary for physicians, who have long addressed heart health from standpoints of nutrition, diet, smoking and exercise, to play a greater role helping patients recognize their risk factors for exposure to pollutants and recommending evidence-based strategies in response, the co-authors argue.

“The first step in preventing pollution-related cardiovascular disease is to overcome neglect of pollution in disease prevention programs, medical education, and clinical practice and acknowledge that pollution is a major, potentially preventable risk factor for cardiovascular disease,” Landrigan and Rajagopalan write in the journal.

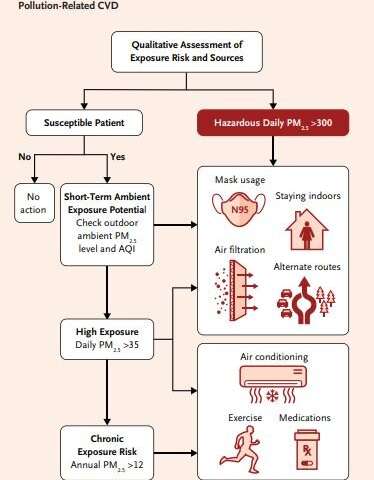

In addition to obtaining patient histories of pollution exposure, doctors can provide guidance on pollution avoidance. They might recommend minimizing exercise on “bad air” days, avoiding exposure on the job, and avoiding the use of pollution-emitting devices—from fireplaces to incense sticks. Preventative recommendations could include the use of facemasks, in-home air cleaners, and air conditioning.

“What has been missing from this whole conversation about cardiovascular disease is the impact of environmental factors outside of an individual’s control,” said Landrigan, a pediatrician and epidemiologist whose pioneering work led to the removal of lead from gasoline. “It is time to bring these issues into the conversation.”

Landrigan, director of Boston College’s Global Observatory on Pollution and Health, added “The scientific knowledge is not brand new. It has been recognized for at least a decade that air pollution and lead are important causes for heart disease and stroke. However, that scientific knowledge hasn’t yet translated to clinical practice in office, hospital at bedside. We think it is time for that to change. We are hoping this will change the practice of individual doctors and NPs, and that it will change the advice that prominent professional organizations give to their members and the public.”

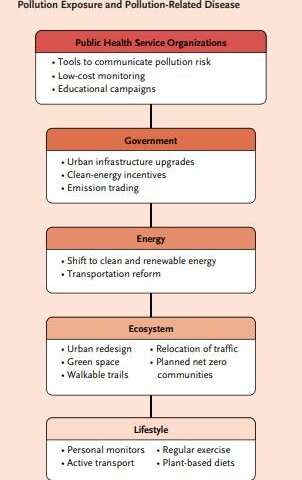

In addition to the call to action for their fellow physicians, Landrigan and Rajagopalan want to bring the issue of pollution to the attention of the world’s leading medical, health, and physician associations to enlist their members in the effort to control pollution. The American Heart Association has already issued guidance on steps individuals can take to protect themselves from air pollution, they note.

But the global scale of the problem is so great that physicians and health care providers cannot be expected to resolve it on their own, the physicians say. Governments, currently grappling with the global response to climate change at the COP26 meetings in Glasgow, Scotland, can use those same efforts to improve cardiovascular health.

“An enduring reduction in pollution-related cardiovascular disease will require more than changing individual behaviors,” they write in the journal. “It will necessitate widescale control of pollution at its sources. The most effective strategy for achieving this goal is a rapid, government-supported transition from all fossil fuels—coal, gas, and oil—to clean, renewable energy. Household air pollution in low-income countries is most effectively controlled by providing poor families with affordable access to cleaner fuels.”

Source: Read Full Article