A simple electrical fan is the key component of a low-cost, easy-to-use breathing-support device designed to cope with the surge in COVID cases in low to middle income countries.

The device provides a form of oxygen therapy called CPAP or continuous positive airway pressure, which has proved effective in helping patients struggling to breathe because of moderate to severe COVID.

In a paper published today (Tuesday, 24 Aug) in the journal Frontiers in Medical Technology, the team developing the device say a pilot evaluation involving ten healthy volunteers has shown that it “…can be used safely without inducing hypoxia (low levels of oxygen in tissues) or hypercapnia (build-up of carbon dioxide in the bloodstream) and that its use was well tolerated by users, with no adverse events reported”.

The researchers used the principals of “frugal innovation” to design and develop the breathing aid, to ensure the device remains simple while being both robust and able to meet clinical demands in poorer-resourced health settings.

A key innovation was to generate the required air flow using a simple electric fan, akin to the fans used to cool electronic devices, to overcome the lack of access to high-pressure air and oxygen supplies.

The device was developed by a team of engineers, scientists and doctors from the University of Leeds, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Medical Aid International and the Mengo Hospital in Uganda.

‘Greater access to critical care technology’

Nikil Kapur, Professor of Applied Fluid Dynamics at the University of Leeds and the supervising academic on the project, said: “By adopting the approach of frugal innovation, we have been able to redesign an important piece of medical equipment so it can function effectively in poorer resourced healthcare settings.

“We have stripped away unnecessary complexity and ensured the device will work in settings where oxygen supplies are scarce and need to be conserved. The prototype is an important step in developing a device that will create greater access to critical-care technology and help save lives.”

Components for the protype device cost around £150 ($207 US). Conventional CPAP machines can cost from around £600—and a ventilator used in an intensive care unit can cost more than £30,000.

Dr. Tom Lawton, Consultant in Critical Care and Anaesthesia at Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and a member of the research team, said: “In the UK, CPAP has been effective as the mainstay of respiratory treatment for severe COVID-19 and helps to keep patients from needing advanced ICU care such as ventilators.

“In many countries, resource limitations mean that even CPAP is difficult to come by and more severe disease frequently leads to death. Simple CPAP devices, designed to operate in a resource-limited setting, can help reduce global healthcare inequality and save lives both now with COVID-19 and potentially with other diseases in the future.”

CPAP—an effective therapy for COVID patients

A recent UK study known as the Recovery-RS Trial has highlighted how CPAP can provide a valuable intervention for COVID-19 and the World Health Organisation is encouraging the rapid development of low-cost breathing aids that could be deployed in poorer-resourced healthcare systems.

For that to be possible, the devices must operate with low pressure oxygen systems. Unlike in richer countries, clinics and hospitals in poorer settings may not have access to centralised oxygen supplies, where oxygen is piped under pressure to wards, or a steady supply of oxygen cylinders.

Instead, they rely on what are known as oxygen concentrators, machines the size of a suitcase that take in ambient air, strip out the nitrogen and provide a supply of oxygen at low pressure.

Prototype CPAP machine works with oxygen concentrators

Dr. Pete Culmer, Associate Professor in the School of Mechanical Engineering at Leeds and the study’s lead author, said: “The Leeds prototype has been specifically made to work with oxygen concentrators, which have a low flow of oxygen and at low pressure.

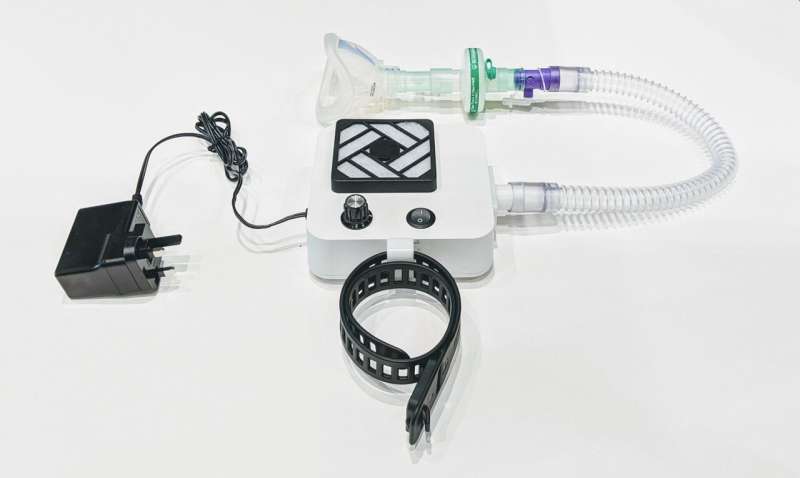

“The fan or CPAP blower is connected to what is known as a breathing circuit. That circuit is made up of a filter to catch viruses and bacteria in the air flow, tubing, face mask, a valve which controls the flow of oxygen from the oxygen concentrator, and an expiration outlet.”

The cleverly designed fan system provides a safe air flow supply without needing more complex—and costly—control systems or a high-pressure air source. This provides a simple and robust means to generate an airflow sufficient to open the patient’s airways, so oxygen can get into the tiny air sacs in the lungs, without risk of adverse effects. The oxygen concentrator is used to enrich this airflow with oxygen, conserving valuable supplies.

The device can generate four different levels of air pressure dependent on clinical need.

The paper says desirable oxygen saturation levels in the blood—between 96 percent and 100 percent—were maintained in the healthy volunteers taking part in the trial. The CO2 range at the end of exhalation was between 3.6 and 4.9 pKA, again within accepted healthy limits.

Professor David Brettle, Chief Scientific Officer at the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust and a member of the team that developed the device, said: “The innovation at the heart of this device is the simplicity of its design, the low production cost and how it efficiently makes use of scarce oxygen supplies.

“In the UK access to the necessary health technology can be taken for granted, but even relatively simple technology is sometimes not available in low-and middle-income countries. This innovative device aims to level the playing field.”

Patient trial due to start in a matter of weeks

A trial involving sick patients is planned to begin at the Mengo Hospital in Kampala, Uganda, next month (September).

Dr. Edith Namulema, an epidemiologist in Uganda involved in the research project, said there is a desperate need for CPAP machines in low to middle income countries.

Uganda has a decentralised healthcare system, with patients being referred from community and district health centres and clinics to regional and national hospitals if they are very sick.

Dr. Namulema added: “It is only the regional referral and the national referral hospitals that have access to CPAP. Yet patients first present to the lower-level facilities when they have breathing difficulties and by the time they arrive to the regional referral centres, in some cases, it is too late. The ability to hook a patient onto ventilation when they need it potentially saves many lives and reduces the hospital stay.

“Also, as a country we have about 500 ICU beds for 42 million Ugandans which is very few.”

Source: Read Full Article