An enzyme that has been identified as instrumental in the progression of many types of cancer is meeting its match in inhibitors synthesized and evaluated by University of Colorado (CU) Cancer Center researchers.

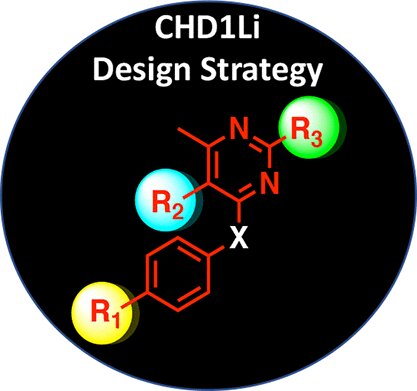

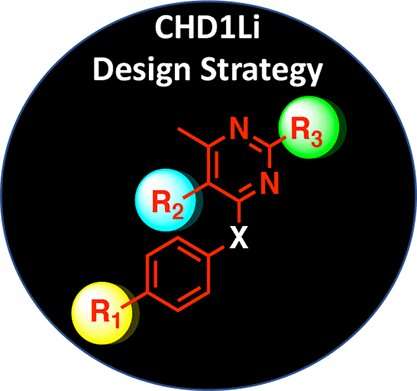

In findings recently published in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, researchers detailed the more than 30 inhibitors synthesized to resist the tumor-causing effects of the CHD1L oncogene, which has been implicated in tumor progression, multidrug resistance, and metastasis in many types of cancer.

“There are no known CHD1L inhibitors reported in the literature,” explains study corresponding author Daniel LaBarbera, Ph.D., a CU Cancer Center member and director of the Center for Drug Discovery in the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. “We have the only known drug leads against this oncogene, so we optimized one of our top lead compounds through drug design and medicinal chemistry with the goal of improving its efficacy and drug-like properties in targeting the CHD1L oncogene.”

Working to inhibit tumor-supporting enzyme

CHD1L, also known as ALC1, was discovered in 2008 and within two years emerged as a novel oncogene. “Its over-expression or over-amplification in many cancers is associated with poor prognosis and with late-stage metastatic cancer,” explains LaBarbera, who also serves as co-director of the Drug Discovery and Development Shared Resource (D3SR). The D3SR is the main infrastructure of the CU Anschutz Medical Campus Center for Drug Discovery and is a CU Cancer Center-supported shared resource lab. “It helps tumor cells progress and then become drug resistant.”

Tumor cells need transcription factors to access sites on DNA to which they can bind and then activate gene expression. CHD1L is recruited to essentially remodel DNA structure and expose these sites. Inhibiting CHD1L has the potential to reverse this malignant cellular state to one that is less tumorigenic and more sensitive to clinical therapies.

Working with a known drug lead that showed promise against CHD1L, after screening about 20,000 drug compounds, researchers modified the drug structure to synthesize analogs that would improve the drug’s efficacy against CHD1L. They also performed molecular modeling using a recently published CHD1L crystal structure to explain how the drug binds to the CHD1L enzyme.

One of the most promising analogs, called 6.11, was also one of the simplest: Researchers added a bromine atom to the base drug, which improved its drug-like properties significantly.

“Oftentimes, if drugs are rapidly metabolized in the liver they lose their activity and are excreted out of the body,” LaBarbera says. “Incorporating bromine into the design improved the metabolic stability compared to the parent lead drug 6.0, which translated to an almost three-fold longer half-life in animals. We went from three hours of half-life in blood plasma with 6.0 to an eight-hour half-life with 6.11.”

That increased half-life is significant because it could lead to more effective drug treatment in humans. “It represents the possibility that a patient could receive treatment once a day instead of twice a day. We also showed that the drugs could be administered orally and still get to the tumor site and have anti-tumor activity,” LaBarbera says. “There’s the potential of developing a pill formulation for this drug that could supplement and synergize with intravenous chemotherapy and other standard of care therapies.”

Supporting drug discovery

As research into developing CHD1L inhibitors continues, scientists are considering how the drug could be used in combination with standard of care therapies, “including radiation and other therapies, where a patient would go home with a prescription for the drug and take it to help prime tumors, wherever they are in the body, for chemotherapy,” LaBarbera says.

The CHD1L enzyme is essential for DNA repair in tumor cells, which is a major mechanism of drug-resistance. Interestingly, researchers have observed that the enzyme’s expression is upregulated in tumor cells, allowing them to make more targeted therapies with the possibility of fewer side-effects.

Source: Read Full Article