The bulge in my pants I expected was nowhere to be found. Kayla, my first high school girlfriend, gazed back at me and brushed a lock of hair from her cheek. Detecting a hint of confusion in her eyes, I ground my pelvis down hard against her. My bedsprings squeaked. I squirmed. But nothing happened.

Still, I let her peel my jeans and boxers down around my ankles. But even with her steady tugging, nothing stirred below my waist. I commanded myself to focus, honing all of my energy on levitating those few inches of skin. But, after a few agonizing minutes, I finally accepted that I couldn’t Houdini the thing to life.

“Sorry, I’m nervous,” I whispered.

“It’s okay,” she said, before eventually falling asleep on my shoulder. But, as I laid there, staring at an image of jousting knights on my bedroom wall, all I wanted to do was reach down and wring its tiny neck. In the following weeks, we kept trying. But each time her hand made the slow descent down my abdomen, I shriveled like a raisin in the sun.

I tried imaging bacchanalian scenes worthy of Caligula. But it did no good. I tried grabbing it myself like a rancher wrestling a steer. But it did no good. Nothing did any good. It was only after she left that I would sheepishly peel open the crinkled pages of my June 1998 Hustler and watch, in shock, as the thing sprung back up like a one-fingered hand flipping me the bird.

Several months into the relationship, she came over on a Saturday night. Halfway through a movie, she began kissing my neck, and I was horrified by the realization that I didn’t even expect to get it up. I was merely waiting for the inevitable to happen. It did. Or, I should say, it didn’t.

After I drove her home, we sat silently in the driveway. Then, I muttered something like, “it’s not you, it’s me”—words I knew sounded fake, but were all I could find.

“It doesn’t matter,” she said, her cheeks flush and her eyes wet. But she couldn’t reach me because my adolescent brain had already drawn its own conclusion: I am not enough.

“My fear and worry reduced me to a sweaty, fumbling mess.”

When she eventually went inside, I sat there, gripping the steering wheel as the minutes passed. At first, I wondered if she would tell her friends about my struggles. Then, I realized she probably already had. My skin grew hot. My stomach churned. But the way I felt in that moment—alone, embarrassed, ashamed—was somehow less painful than the unbearable prospect of failing all over again.

Erectile dysfunction. The term often evokes an image of a silver-haired man sipping Mai Tais in Florida with his fourth wife. But a striking number of men under forty grapple with the condition. Many cases go unreported, making its prevalence remarkably hard to pin down—estimates range from 2% to a staggering 40%. The root of the problem can be medical, but, more often, these cases are deemed to be psychological in nature.

“Anxiety is the enemy of arousal,” says Ian Kerner, renowned sex counselor and author of She Comes First. Failing to perform, especially during early sexual experiences, can cause what he calls “trauma with a lowercase t.” It isn’t the same as, say, becoming the victim of a violent crime. But the stress, guilt and shame that result from these developmental traumas are stored in the body and brain and can lead to a self-feeding cycle.

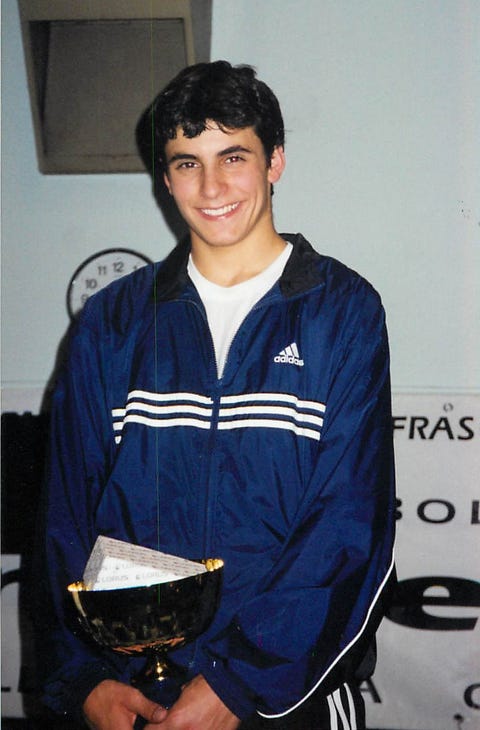

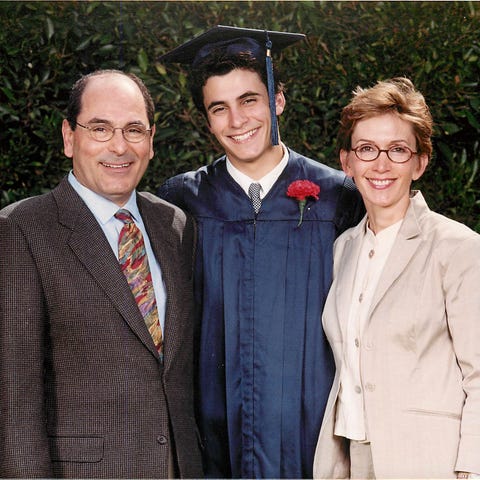

Although I was never a particularly angsty kid, my sexual troubles with Kayla reigned in my youthful exuberance. Unlike my friends who chased girls and generally enjoyed the teenage hormone rollercoaster, I focused on fencing and school—an effort that led to a full scholarship at The Ohio State University. After I left Los Angeles for Columbus, I quickly established myself as an Olympic hopeful and, despite spending upwards of two months abroad for competitions, maintained a near 4.0 GPA.

But the self-assurance I drew from those achievements never crossed over to the bedroom. There, my fear and worry reduced me to a sweaty, fumbling mess. Each time it happened, I did my best to banish the event from my mind. But I also began to feel that if I couldn’t perform in that realm of my life, I had to make goddamn sure that I was perfect in all the others.

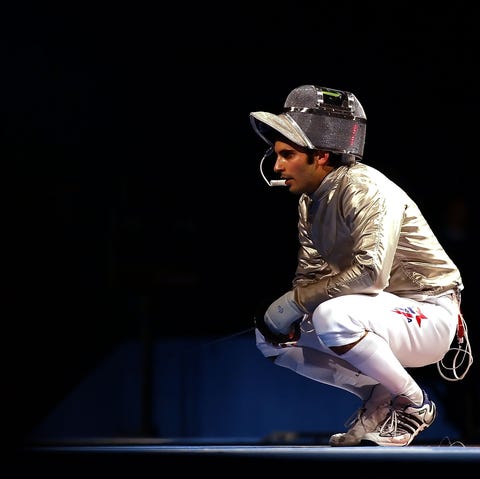

In 2004, I qualified for my first Olympics at the age of twenty-one. Achieving my childhood goal and representing the United States was thrilling, to say the very least. But only moments into my debut event in Athens, I sensed a tingling emptiness in my temples, as if the blood was draining from my head. An impenetrable psychic wall built itself around me causing my fencing to deteriorate rapidly.

My opponent, a cocksure Italian (imagine the quintessential soap-opera stud that makes even your grandma hot and bothered) defeated me swiftly and without mercy. The score of our match, 15-3, registered among the worst fencing losses at those Games. But it was the way I lost—dominated by such an alpha male—that returned a familiar feeling: I am not enough.

Afterward, I found an empty, concrete hallway in the bowels of the arena. Although I tried to remind myself that it was an honor just to compete, all I felt was failure. Quivering as thick tears sloshed down my cheeks, a single, deluded question tore through my mind: If I can feel this impotent when I’m supposed to be strong, how can I possibly respect myself as a man?

The Athens Olympics left me emotionally concussed. In addition to my ass-kicking, I received another blow several days later during our team competition after we fell short of a medal by a single point. But when I replayed the memory of that first event, I couldn’t help but note its eerie similarity to my experiences in the bedroom. The emotional sequence was the same: powerlessness, horror, shame.

I seriously considered leaving the sport, but ultimately decided to continue fencing in hopes that I might redeem myself at the next Games. After graduating from college, I moved to New York and doubled down on my training while also diving deep into sports psychology to stabilize my wobbly psyche.

Despite a tumultuous qualifying season, I earned a spot on 2008 Olympic team. But in Beijing, more eerie similarities appeared. Like in Athens, I lost 15-3 in the individual competition, this time to my own teammate. But now accustomed to these types of disappointments, I put it behind me, focusing all of my energy on my next event only a few days later.

On the day of the team competition, my stomach churned as the four of us walked out into the arena. In our first match, we overcame a large deficit to defeat our higher-ranked opponents. In the next, we, again, stormed from behind and tied up the score, with only one point to go and a medal at stake.

With our team captain in control of the last stage of the match, I could only stand by and watch as he launched into the air, body stretched, arm extended. He hung there for what seemed like ages before the tip of his saber struck his opponent’s mask with a satisfying thwack. Realizing he—we—had secured the win, an emotional fissure tore open within me, like a geyser releasing untold years of geological pressure. I would be an Olympic medalist.

The days, months, and year that followed unfolded in a blur. My silver medal brought new opportunities, earning me access to spheres I never thought possible: galas, celebrity parties, fashion shows. I began working as a model, represented by the New York agency Wilhelmina. The future looked bright. But a part of me remained agitated, unsettled.

On a trip home, I went out to a Hollywood club with friends. At the bar, I met an attractive woman with sharp sense of humor. After a night of drinking, we went back to my place. My confidence soared, not only from alcohol but also the tin foil wrapper in my pocket containing a new, secret weapon I recently got from my doctor: Viagra.

“I’m an Olympian, and I can’t even fuck?”

Having covertly popped 50 milligrams of boner magic in the taxi, I was ready to go soon after we arrived. But about a minute after we started having sex, the finish line, which once sped towards me, began extending farther and farther away. So, I did what any athlete does: Try harder.

But the faster I went, the more out of control I felt as if sprinting on a treadmill moving too fast. When I finally admitted defeat, I buried my face deep into the pillow. “Well, I’m satisfied,” she said in the way no man ever wants to hear. I’d have burst out laughing if I weren’t preoccupied with a darker thought: I’m an Olympian, and I can’t even fuck?

Shame is a toxic emotion that leads men to keep their sexual troubles to themselves. A survey commissioned by a UK-based pharmacy chain reported that 43% of men said that they didn’t feel they could discuss the issue openly with friends. And over a quarter would prefer to break up with a partner than to seek treatment from a doctor.

If these numbers shock you, they shouldn’t. Just look at how western culture shapes the dialogue around sexual performance. Hollywood celebrates young, virile heroes. Porn paints an unattainable portrait of male sexual performance. Even telemedicine startup Roman promises to ship men ED medication in “discrete packaging” and to their “friend’s” door. Through these influences, men learn, implicitly, that sharing their troubles will only compromise their masculinity and lead to embarrassment.

My initial attempts to talk about my sexual troubles taught me a similar lesson. One night, in my early 20s, I broached the topic with a childhood friend. A muscle twitched in the fleshy skin under his left eye before he spoke. “Well, I don’t struggle with that,” he said, bringing our conversation to an abrupt end.

That reaction—the way he snapped shut like clam sensing danger—was one I had experienced before. It resembled a time I tried to open up to a fencing teammate about choking at a crucial national tournament. As soon as I began my story, he cut me off. “Don’t worry about it,” he said. But from the way he recoiled—as if my words were contagious—I understood his meaning: Don’t put that shit in my head.

My failure with the Hollywood girl had torn a final hole in my ragged sexual confidence, leading me to do something I never I thought I’d do: Talk to my dad. My resistance was never due to a bad relationship between us. Although he traveled a lot for work and took a more reserved approach to parenting, he could, at times, be very dad-like and supportive.

It also extended beyond the natural allergy every young boy has to talking to his parents about sex (ew). Instead, it had more to do with my fear of revealing to the very man that gave me life, something that I thought compromised my own manhood.

But, sitting at a corner table at an empty restaurant in New York City, I finally did. After I told him everything, I braced for the same whiplash of judgment I had felt so many times before. “I’m so sorry,” he said with a heavy sigh, “I wish we had this conversation a long time ago.”

Relief rushed over me as he began, haltingly at first, to reveal his own battles with sexual performance anxiety that first arose during a period in college, and again after the end of his first marriage. Like me, he had compartmentalized the issue, concealing it from others, especially his male friends. But he also emphasized that he regretted keeping it to himself.

“At my age,” he said, “you learn not to give a shit about the people that don’t love and support you no matter what.”

The initial confidence I built from that conversation led to others. I began having regular sessions with a psychologist and grew more comfortable peeling back the layers around my feelings. I found and invested in new male friends that I could count on to react to my revelations without defensiveness or self-recrimination. When the issue arose in new relationships, I learned to be honest and share rather than shut down my emotions.

I also pushed myself to explore more openly. For a brief period, I even dated several men after wondering whether I was in denial about some part of myself. That experience didn’t offer the solution I’d hoped to find, but it did teach me to view sexuality not as a binary choice but, instead, as something that falls on a spectrum.

Now 36, married, the issue largely behind me, I find myself reflecting often on who I might have been without this personal battle. I’ll admit, there are still times when anger flashes as I think about all the youthful pleasures spoiled. But far more often, I’m grateful for my experiences because they taught me to be considerate, introspective and suspicious of hubris, both in myself and others.

But don’t misconstrue my meaning. My fingers tremble as I type these final words and consider the prospect of so many people reading these disclosures—including some of my own family and friends that remain in the dark. But I’m comforted by the fact that I now know that I can be competitive and gentle, strong and sensitive, confident and vulnerable. None of those apparent contradictions make me any less of a man.

Source: Read Full Article