Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), or dysmorphophobia, is a mental disorder that provokes the individual to focus unduly on flaws in the personal appearance to an extent that it dominates thought, producing severe embarrassment, shame, and anxiety such that the person may even avoid social situations. This is despite the fact that these alleged flaws are not obvious to other people, or are negligible.

The severity of this disorder can cause markedly lower quality of life. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-4 (DSM-IV), BDD is “a preoccupation with an imagined defect in appearance; if a slight physical anomaly is present, the person's concern is markedly excessive.”

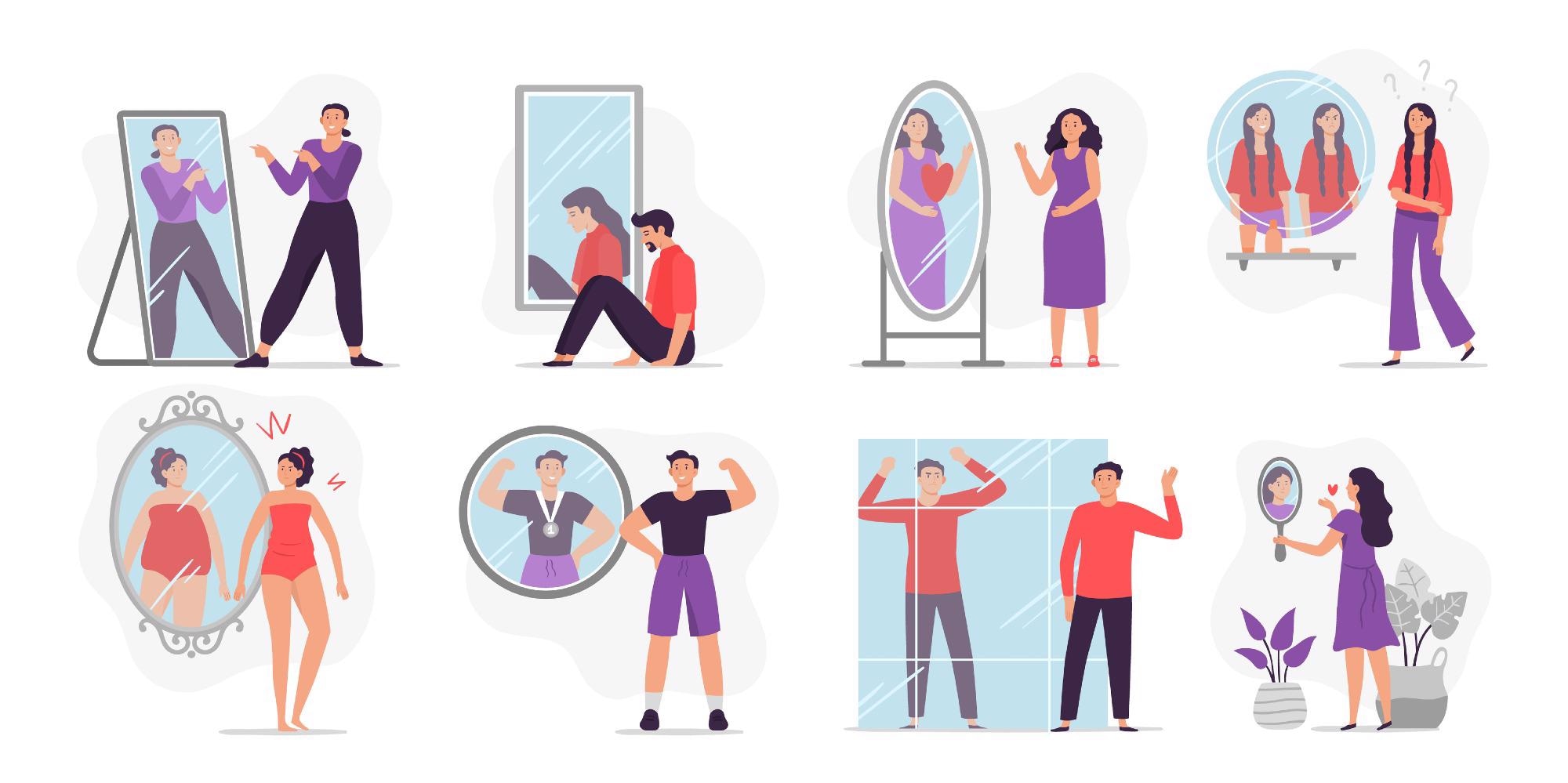

Image Credit: Reksita Wardani/Shutterstock.com

What Are the Symptoms?

The presence of BDD leads to an intense obsession with your appearance, also called body image. Such individuals tend to check the mirror all the time, either to correct imaginary flaws or to reassure themselves that they look all right. This process could occupy hours of each day.

Some body features that are commonly the focus of such unhealthy fixations include the face, nose, complexion, acne, hair, breast size, muscle size, and genital organs.

While some degree of insecurity about one’s appearance is normal, the major distress caused by such thoughts in BDD, together with the repetitive actions or behaviors it provokes, is characteristic of the condition. In fact, it may hamper normal functioning in day-to-day life, with feelings of rejection, shame, and unworthiness.

Most people with BDD are not married and many cannot hold down a job. Many BDD patients do not finish school or stop working.

No matter how many times reassurance is offered that the defect is not present, or who offers the reassurance, such individuals continue to believe that this is the case and to think of themselves as ugly or deformed. Moreover, they are under the delusion that others notice them only to think of them as unattractive or to mock them for this.

For instance, some think of themselves as extremely fat, despite the fact that they are underweight. Others may consider their acne outbreaks to be the focus of attention of everyone around them, resulting in their picking at pimples all the time, repeatedly checking the mirror to make sure their acne is camouflaged perfectly, or using more make-up to disguise it.

Such individuals may also avoid mirrors or try to hide the so-called ugly part under makeup or a clothing accessory. Comparisons with other people are constantly ongoing, along with an avoidance of social exposure, to the point where they become housebound, venturing out only at night when it is too dark for anyone to see them properly.

Some common coping measures include, as seen above, constant mirror checking; excessive grooming; camouflaging; changing clothes frequently; seeking constant reassurance; picking at the skin, and restricting one’s diet beyond reasonable limits. These behaviors occupy a major part of the day, every day, and are almost irresistible for the patient.

Other outcomes may include quite unnecessary cosmetic surgery to correct these so-called defects. Such procedures provide a sense of relief or satisfaction for a time, but unfortunately, once it wanes the individual continues the old behaviors.

These people constantly compare themselves with others, always to their disparagement, and need to hear from others that they look fine, especially with respect to the offending feature. They are perfectionists and cannot overlook minor defects without major guilt or shame.

While some people with BDD recognize that their fixation is abnormal or false, up to half lack this insight – they are delusional. The strength of the false belief determines the extent of disruption of normal life.

What Are the Risk Factors for BDD?

BDD is present in 0.7-2.4% of the general population, though this is likely to be a gross misdiagnosis.

Adolescence is the period of highest risk for the onset of BDD. People who were teased about their bodies, neglected, or abused in early childhood appear to be at especially great risk, as are those with perfectionistic tendencies. Individuals who grow up in a society that puts a premium on beauty are also more likely to develop BDD, especially those with other mental ill-health conditions like depression or anxiety.

Having a family history of BDD, abnormalities of brain chemistry, a perfectionistic personality type, and poor childhood experiences relating to the body or self-image may all contribute to the condition.

BDD may lead to other complications such as major disorders of mood, obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating disorders, or substance abuse. The person may think suicidally and even behave in this manner, in up to 80% and 25% of cases, respectively. Anxiety disorders and social phobias are also observed to be more common in this group.

The individual may be in significant pain or undergo disfigurement due to repeated surgical procedures. Less than one in ten show improvement with non-psychiatric measures, including surgery. The lack of satisfaction with the outcomes may lead to suicide in a few cases or violent attacks on the treating physician

BDD symptoms may vary slightly with the baseline culture, but the fundamental expression seems to be universal. BDD in adolescence is associated with greater delusional behavior, current addictions to substances, and suicidal behavior.

Neuro-imaging studies are ongoing but no definitive conclusions have been reached. Information processing appears to be defective, which agrees with the high prevalence of delusions or ideas of reference.

Image Credit: Tartila/Shutterstock.com

How is BDD Managed?

BDD is unlikely to improve on its own and may worsen over time. This may lead to severe anxiety, the need for intensive medical treatment and high medical bills, serious depression issues, and thoughts of, or attempts to commit, suicide.

While people with BDD are unlikely to think of themselves as having a medical problem, it is important to identify such issues and ensure they receive treatment. The diagnosis is arrived at if the individual is unduly and constantly worried about a minor or imaginary body flaw, such that normal functioning is hampered.

The identification of risk factors for BDD does not mean it can be prevented, but early diagnosis and treatment may prevent complications from setting in. BDD is typically a missed diagnosis, though it is twice as common as OCD and is more common than some phobias and eating disorders. Somatic symptoms are rare, and the presenting symptoms may be a social phobia or panic attacks, again leading to the overlooking of the true diagnosis.

BDD is diagnosed in people who are 1) concerned about a minimal or nonexistent defect in their appearance, 2) think about it for an hour or more every day 3) experience clinically significant distress or impaired functioning as a result of their concern.

Therapy may be required long-term to keep the patient stable. If the patient is delusional, the message that treatment may reduce their suffering is likely to be more helpful than telling them they have a mental health disorder.

This may include assessing the extent of the problem, the suitability of various therapies or procedures or medications based on individual susceptibility, personal preferences, the opinions of the medical professionals involved in the case, and the prognosis. Psychotherapy and medications are the most commonly used combination.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is found to be among the most effective psychotherapies, where unpleasant and unproductive thoughts are replaced by positive thoughts. This skill is learned in sessions with psychologists and mental health therapists.

Some individuals may benefit from antidepressant use, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), that are the treatment of choice in this condition. SSRIs may be required at relatively high doses and for a longer time before their beneficial activity sets in.

References:

- Phillips, K. (2004). Body Dysmorphic Disorder: Recognizing and Treating Imagined Ugliness. World Psychiatry. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1414653/

- Bjornsson, A. S. et al. (2021). Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181960/

- Body Dysmorphic Disorder (2021). Retrieved from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/body-dysmorphic-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20353938. Accessed on October 25, 2021.

- Body Dysmorphic Disorder (2021). Retrieved from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/body-dysmorphic-disorder. Accessed on October 25, 2021.

Further Reading

- All Mental Health Content

- World mental health support and the effect of stigma and discrimination

- A Guide to Coping with Change

- Managing and Reducing Stress

- Analyzing the Stigma Surrounding Mental Health

Last Updated: Jan 24, 2022

Written by

Dr. Liji Thomas

Dr. Liji Thomas is an OB-GYN, who graduated from the Government Medical College, University of Calicut, Kerala, in 2001. Liji practiced as a full-time consultant in obstetrics/gynecology in a private hospital for a few years following her graduation. She has counseled hundreds of patients facing issues from pregnancy-related problems and infertility, and has been in charge of over 2,000 deliveries, striving always to achieve a normal delivery rather than operative.

Source: Read Full Article