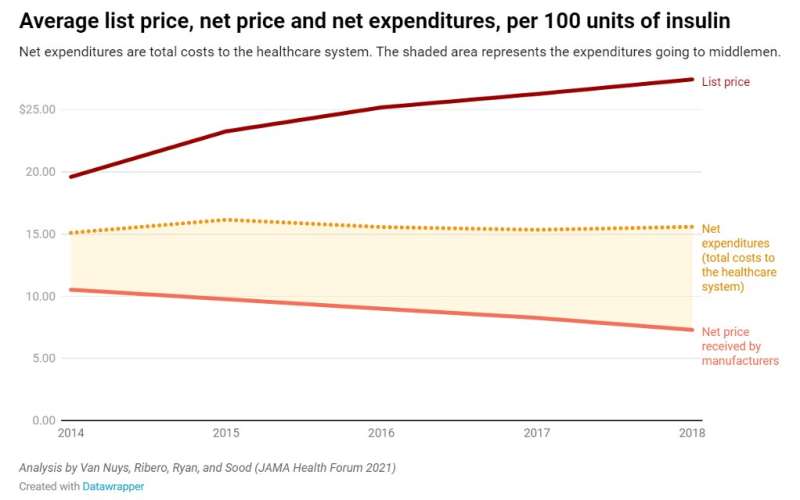

Despite its discovery nearly 100 years ago, insulin’s list price has been going up, not down, with trade secrets and other protections preventing researchers from pinpointing who is receiving profits from its sale. Meanwhile, the net price—what manufacturers receive after accounting for all discounts and payments to distribution system entities—has been falling. So, why aren’t patients seeing the savings?

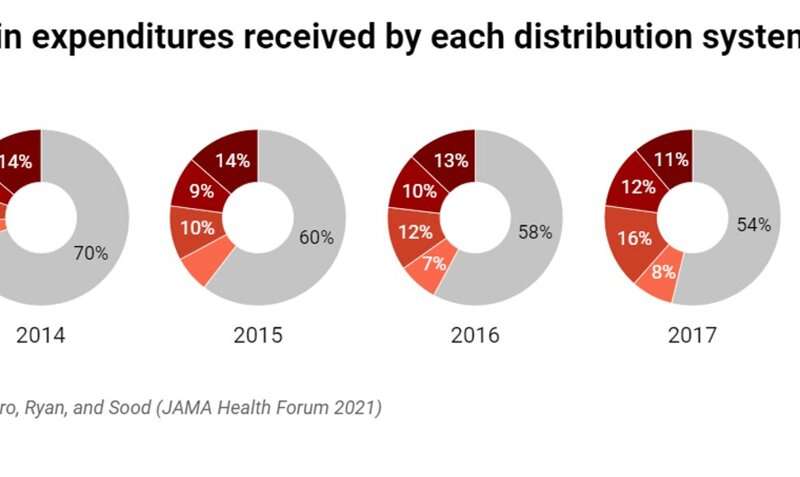

The researchers analyzed the flow of money across all distribution system participants—manufacturers, wholesalers, pharmacies, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), and health plans—and find that middlemen in the distribution process now take home approximately 53% of the net proceeds from the sale of insulin, up from 30% in 2014. Meanwhile, the share going to manufacturers has decreased by 33%.

This redistribution of profits has led the total cost to the healthcare system—net expenditures — to remain relatively flat.

“Although manufacturers have been receiving less, the savings from manufacturers taking less are not flowing to patients,” said Karen Van Nuys, executive director of the Value of Life Sciences Innovation Project at USC Schaeffer Center. “Those savings are being captured by others in the distribution system, and any policy solution has to look at the entire supply chain.”

The insulin distribution system: A complicated web

To understand how money in the insulin distribution system has flowed over time, Van Nuys and colleagues Rocio Ribero, Martha Ryan, and Neeraj Sood leveraged 15 different data sources to create a database of insulin expenditures between 2014 through 2018.

Of a hypothetical $100 spent on insulin, they find manufacturers accrued about $70 in 2014, falling to $47 in 2018. During this time, the share going to pharmacies increased from about $6 to $20, PBMs’ share increased from $6 to $14, and the share going to wholesalers increased from $5 to $8. The health plans’ share had decreased from $14 to $10 per $100 spent on insulin.

“Clearly all entities in the pharmaceutical distribution system profit from the sale of insulin,” said Schaeffer Center Senior Fellow Neeraj Sood. “But these data suggest increasing profits to intermediaries in the system are playing a key role in keeping net expenditures high.”

Building a unique data set

Due to lack of transparency in the system, the researchers had to leverage several sources to develop a data set that enabled them to map expenditure flows at each step in the distribution system. Sources included data from Medicare and Medicaid, Securities and Exchange Commission filings as well as state-level audit reports that were the result of state drug pricing transparency laws passed in recent years.

“It is telling that we had to combine data from more than a dozen sources to understand expenditures on a single class of drug over a 5 year period,” said Ribero, research scientist at the Schaeffer Center.

Regulation should target all players in the distribution process

About 9.1 million Americans with diabetes require insulin to effectively to manage their disease. Patients without insurance as well as those in high deductible health plans have increasingly felt the burden of high and rising list prices, sometimes with fatal consequences. Policymakers have taken note.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services recently introduced a model that would limit out-of-pocket expenses to $35 per thirty-day insulin supply. While the researchers note that such steps would provide immediate financial relief to patients, they would not address the overall cost of insulin to the system, or the outsized market power and influence of middlemen.

Many intermediaries in the system operate in highly concentrated markets where they can influence prices, conclude the researchers. In 2018, the three largest PBMs accounted for more than 70% of all prescription claims, and the top three wholesalers accounted for 95% of distribution revenues.

“Clearly there are issues throughout the system,” said Van Nuys. “Policymakers should bring together all players in the distribution system, require a transparent accounting of financial flows at each step, and from there develop solutions that improve health and system-wide affordability.”

Source: Read Full Article