Governments and organizations around the world are mulling the use of hotly-debated “immunity passports” aimed at easing pandemic-related lockdowns and restrictions on movements.

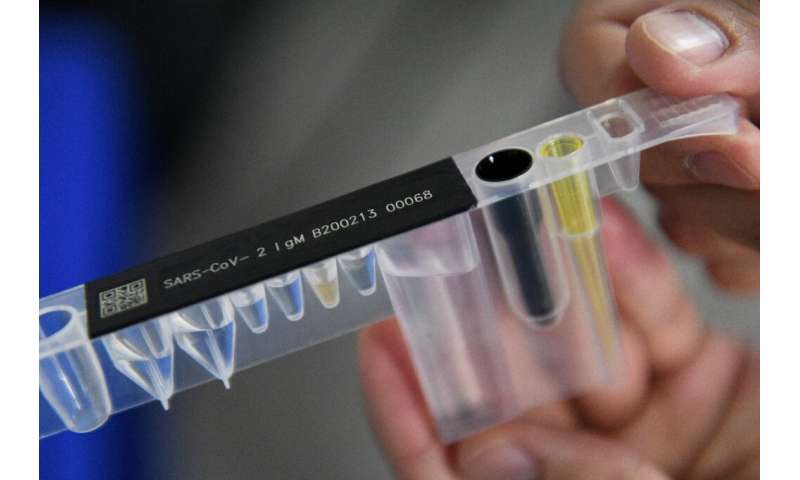

The certificates could identify people with antibodies that reduce the risk of they will spread the deadly coronavirus, helping them to resume activities and return to work.

But global health authorities and experts are urging caution, pointing to concerns over the accuracy of antibody tests as well as privacy fears and the potential for abuse.

Backers of the idea say the people who qualify could receive digital certificates displayed like smartphone boarding passes, or on paper.

“If this situation lasts six months or nine months, or if there is a second wave, you can assume people will want to leave their homes,” said Husayn Kassai, chief executive of the digital identity startup Onfido.

“There needs to be some mechanism to verify a person’s immunity. The immunity passport, if it works effectively, is more likely to help people comply with staying at home.”

Onfido, which has been in talks with the British government and other authorities, said immunity would be determined by a home testing kit similar to those used for pregnancy tests and validated by health authorities.

These could flash as green for fully immune, amber for partly immune or red for risky. The results could be modified in a database if needed, according to Kassai.

British-based startup Bizagi has a “CoronaPass” developed for businesses to screen employees, but CEO Gustavo Gomez says “it could help a lot more people” return to activity.

French tech startup Socios is developing an immunity pass for sporting events so that “only fans who are at low or zero health risk are initially able to attend matches,” according to its website.

Chile this month began issuing certificates to people who have recovered from COVID-19; talks on similar efforts are ongoing in Germany and elsewhere.

Accuracy unclear

The World Health Organization recently issued a warning that there was “not enough evidence” to give people “risk-free certificates,” but hours later appeared to backpedal with a modified statement.

In the follow-up, WHO said it expected that people who are infected with COVID-19 “will develop an antibody response that will provide some level of protection” but added that “what we don’t yet know is the level of protection or how long it will last.”

Claire Standley, a research professor specializing in public health at the Georgetown University Center for Global Health Science and Security, said she was skeptical of the certificates in part due to the “lack of certainty over the extent to which antibodies offer protection against reinfection.”

University of California-San Francisco pathologist Alan Wu also sounded a note of caution.

“Everybody wants to be believe that if I have antibodies, I’m immune,” said Wu. “Well, we can’t be certain of that. The antibody test for this virus hasn’t been around long enough to show that nobody can get infected again if they have antibodies.”

Privacy concerns

The idea of immunity certificates is not new. Children who get vaccinations for measles, polio and other diseases often must show certificates to attend schools.

The adult film industry used a system for several years called SxCheck that provided certificates to show performers were free of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

Some fear a stigma against those who are not immune, from systems developed in China where a person’s status is displayed on a device.

But firms specializing in digital identity maintain that it is feasible to create immunity certificates without sacrificing privacy.

Kassai said that privacy could be maintained by using QR codes, read by a scanner and associated with a person’s photo.

“Immunity passports prove that you are who you claim to be and the test results belong to you. You don’t need to share any more information,” said Kassai.

Dakota Greuner, executive director of ID2020, a consortium of digital identity organizations and focused on privacy, said any certification program should be done “using identity technology that places control of private data in the hands of the individual.”

But the passports could create other issues—such as, according to Standley, a perverse incentive for people to deliberately infect themselves to obtain a certificate, allowing them to return to work or normal activity.

“There are people who are legitimately struggling, economically and socially,” she said. “The longer the restrictions continue, the more likely it is, I would think, that people may consider risking their own health if they see a potential way out of lockdowns. “

The deployment of immunity certifications would be “a spectacularly unsuitable path that is unlikely to be useful and is likely to be harmful,” said Jules Polonetsky, chief executive of the Future of Privacy Forum, a Washington advocacy group.

Source: Read Full Article