As a star student and a promising athlete at her Mississippi high school, with college ambitions, it seemed that the sky was the limit for then-17-year-old Katie Stubblefield, her father said.

“She was driven for a purpose,” her father, Robb Stubblefield, told “Nightline.” “When she was a kid, she played soccer from the time she was, what, 4 years old? And she was not very nice at playing soccer … they used to call her ‘bulldozer.'”

But amid the stress of looking at colleges and looking ahead to graduation, the teen’s life took a detour.

Now, four years later, she has a different story to tell — one that describes the emotional struggles of adolescence, the permanence of split-second decisions and how two troubled souls came together to create a second chance.

This story will be featured in an upcoming “Nightline” report. Watch “Nightline” weekdays at 12:35 a.m. ET on ABC.

For Katie, it started with a broken heart and a gun.

That led to her fighting for her life.

At age 21, Katie became the youngest face-transplant recipient in the United States, and only the 40th person to undergo the surgery.

Years before that history-making procedure, she was experiencing a stressful year. The high school senior was suffering health problems related to an appendectomy. Both of Katie’s parents had lost their jobs, teaching at her high school.

“I think really with Katie, she absorbed it, and it hit her deeply because I was her teacher,” Robb Stubblefield said.

Then on March 25, 2014 , Katie’s boyfriend broke up with her. Angry and upset, she left school early and drove over to her older brother Robert’s house.

“I was like, ‘What are you doing home from school?'” Robert Stubblefield said. “So, you know, I called my parents, like, ‘Hey, just so you know, she’s at my house right now.'”

Katie’s mother, Alesia, had been out with a friend and was dropped off at Robert’s house. She tried to comfort her daughter, but Katie didn’t want to talk.

Robert and Alesia went outside to talk to Alesia’s friend, when Robert said it sounded like a door slam. They went in, and the bathroom door was shut. Katie was on the other side.

“I tried to open the door,” Alesia said. “I said, ‘Katie?’ And, nothing. And then I said, ‘Katie.’ I said, ‘Are you OK?’ And about the third time I said, ‘Katie,’ that’s when my heart began to just palpitate.”

“At that point I smelled gunpowder because it was, obviously, indoors and you can smell it,” her brother said. “And I knew exactly at that point what had happened.”

In an impulsive teenage instant, Katie had taken her brother’s hunting rifle, put it under her chin and pulled the trigger.

“I screamed, ‘Katie, no!’ Ad my mom tried to walk in. I pushed her out,” Robert Stubblefield said. “She was dead as far as I was concerned.”

Alesia called her husband at work to share tell him Katie was gone. Robb rushed over to the house, where first responders initially feared the worst. But suddenly there was hope.

“They get in there, and the next thing we hear, through a chain of voices, is, ‘She’s alive. We have a pulse,'” Robb Stubblefield said. “And just like that, the whole world turned on a dime.”

Katie was rushed to the emergency room. Somehow, she could still speak.

“When she was in that ER … she said, ‘Tell my mom and dad I love her — love them. I’m sorry,'” her father said. “It took a lot of strength.”

Not knowing if she would make it, doctors began reconstructing Katie’s disfigured face. From the first night she was brought into the hospital, Robb Stubblefield said the trauma surgeon told them a face transplant would be her best chance at normalcy again.

“He said, ‘This is the worst wound I’ve ever seen, and I think the only thing that will give her any kind of life again will be a face transplant,'” Stubblefield said. “That was the first time we’d ever heard that term.”

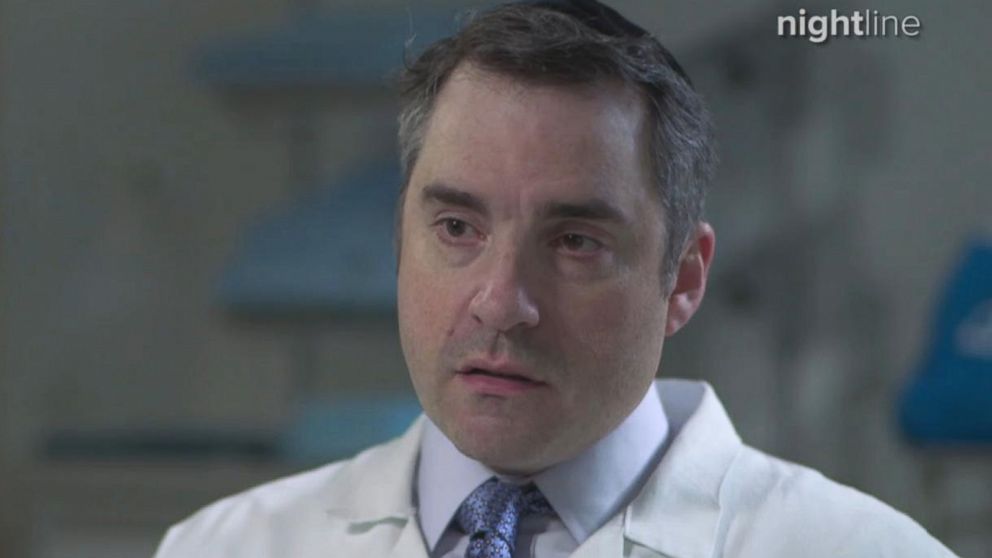

After a month at a trauma hospital in Memphis, Katie was transferred to Cleveland Clinic. Plastic surgeon Brian Gastman was the first to see her. He said at the time that he was not confident Katie would survive, but he was impressed by her will to live.

“Katie was a fighter. I think this was a unique, singular event in her life, and she was willing to overcome it,” Gastman said. “Not just to be alive, but to live her life.”

Cleveland Clinic is where the first face-transplant surgery was performed in the U.S., led by the hospital’s plastic surgery chair, Frank Papay, in 2008. The team has learned a great deal about this type of surgery since then. Before Katie’s case, the hospital had performed two other face transplants.

“And we learned a lot about what it takes,” Papay said. “Not just the surgery of a face transplant, but thereafter. What it takes to monitor these patients. What it takes for the family and support group to help monitor these patients. ”

Gastman was part of the team that performed Cleveland Clinic’s second face transplant. He said Katie’s not the first transplant patient who had attempted suicide.

“Being 17, 18 years old, without any history of depression, with having the type of family support that she has, it seemed that she just did something impulsive,” he said. “We see people doing impulsive things all the time, we just don’t hear about it as much, because they don’t end up in Katie’s situation and then lead to something as fantastic as a — as a face transplant.”

When Katie first arrived in Cleveland four years ago, she and her family moved into the Ronald McDonald house to be close to the hospital for Katie’s constant care, including more than 17 surgeries before her face transplant.

For one of those operations, doctors made a 3D model of Katie’s sister’s jaw to help them reconstruct her face.

The surgical team also took skin from her leg to help reconstruct her nose. All the while, they waited for a donor face to become available.

Katie could have survived with the face the team was able to reconstruct for her, but she wanted to feel normal again, even if that mean risking serious complications — or even her life.

In March 2016, she was officially placed on the face-transplant list. She and her family waited patiently.

“She said, ‘Well, then I’ll just have to get the best reconstruction and I still want to live,'” Robb Stubblefield said. “She didn’t just want a face back. She wanted function … her life back.”

Two years ago, National Geographic began documenting Katie and her family as they awaited a donor for their September cover story, “Katie’s Face.”

In May 2017, after a year of being on the transplant list, a potential donor came through.

Her name was Adrea Schneider, a 31-year-old single mother who had struggled with addiction and died of an overdose.

“Based on all her facial characteristics, her size, age and her basic orthology, she’s a very good candidate,” Gastman said. “She’s a 31-year-old, about nine years older than Katie, individual, a good-sized match.”

Schneider had been raised by her grandmother, Sandra Bennington, who had to make the profound decision of donation. Schneider was registered as an organ donor, so Bennington agreed.

“If Adrea was willing to donate her organs, why would she need a face?” Bennington told National Georgraphic. “I still wrestle with that every now and then, it was something. I don’t know. But this is the right thing to do so that someone else can have maybe a better life. That’s what made my decision.”

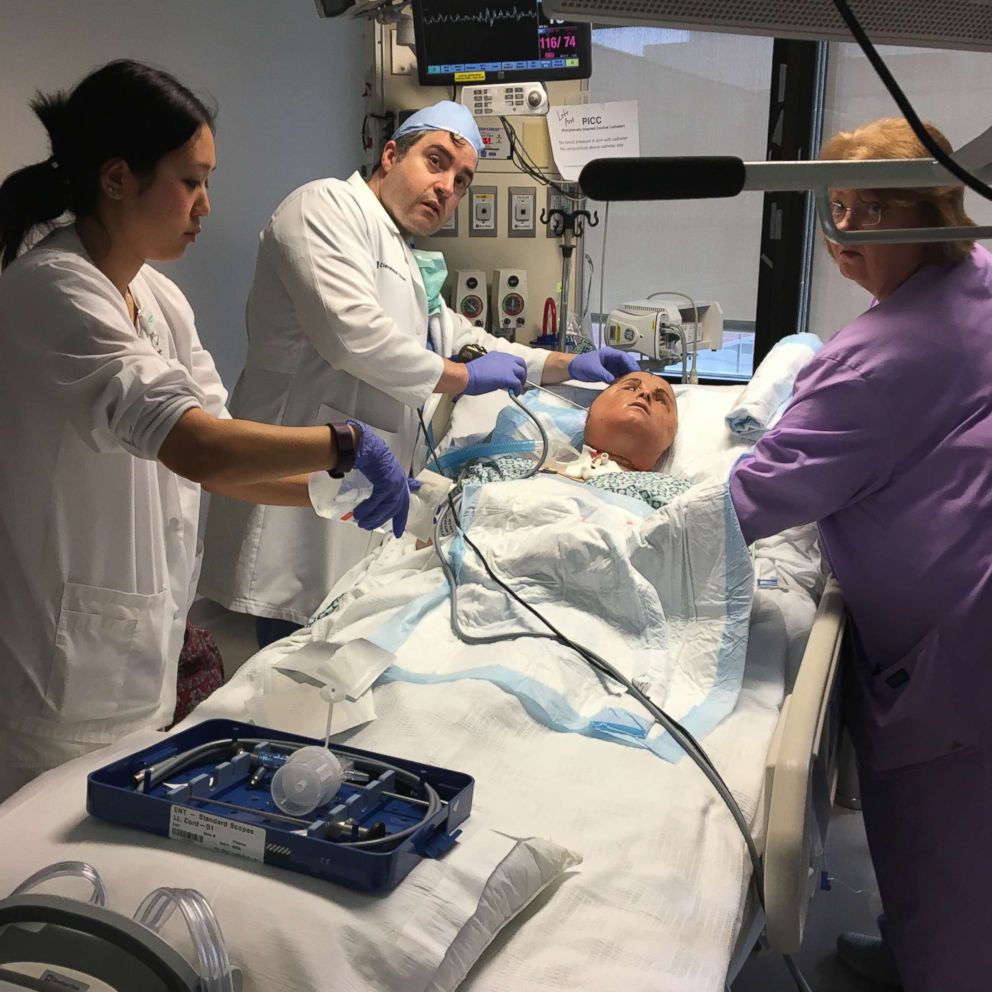

The day before Katie’s operation, the surgical team, made up of more than 50 personnel including 11 surgeons, met to walk through the procedure.

Katie thanked Gastman for giving her a second chance at life before was wheeled into surgery on May 4, 2017. The planned 30-hour surgery was supposed to be for a partial face transplant, but around hour 24, the team felt confident it could move forward with a full transplant.

Gastman and Papay asked Katie’s parents for permission to attempt the full face transplant before proceeding. Robb and Alesia Stubblefield had to weigh what their daughter would want a completely new face, as opposed to just a portion. They decided to go for a full face, and the surgical team went for it.

After 31 hours on the table, with intricate nerve endings and blood vessels restored, Katie finally had her new face. Her parents and brother were able to visit her in recovery afterwards, and see their daughter’s new face for the first time.

“I knew she wasn’t going to look like her old self anymore with that, but I was still — I was speechless,” Robert Stubblefield said.

Katie said she doesn’t remember her life-changing accident. But now, after more than a year of grueling rehab, Katie still has a long way to go.

“When I touch my face now with my hand, I feel whole again,” she told “Nightline.” “I wanted my face back, and I was willing to whatever it took to get my face back.”

“Before my transplant, people looked at me like I was disgusting,” Katie continued. But now “I can go out in a crowd, and people will just see me as another person and not as some kind of monster.”

Katie is still adjusting to life with a new nose and lips — and a new outlook. Now 22, she still doesn’t have her vision back, but she said it’s improving.

“I think that I see shadows — silhouettes, figures,” she said.

Four years after first arriving in Cleveland, the Stubblefields still live in the Ronald McDonald house. Her parents oversee everything with Katie, from her therapy to her anti-rejection medications. But through the ordeal, it’s clear to them that Katie has never lost her essence — and her wicked sense of humor.

“Obviously,” Robb Stubblefield said, “she does not look like her old self, but her actions, her personality, her interests and everything are very much the old Katie.”

Katie still has to undergo more procedures, including getting a new palate, which will enable her to improve her speech. But the health risks of being a face-transplant recipient are never far away.

Just last month, Katie was rushed to the emergency room at Cleveland Clinic because her feeding tube had fallen out, leaving her with a painful wound on her side.

There are also the extensive medical costs, which are in excess of $1 million. Katie’s operation and much of her care are being covered by the Department of Defense as part of its research to find ways of helping wounded soldiers. Since it’s still an experimental procedure, insurance does not cover any of the costs related to Katie’s face transplant.

“The type of wound she had, where it was located, the age factor, is just so classic of what these soldiers go through,” Robb Stubblefield said.

Katie did get the chance to thank her donor’s grandmother in person for giving her a new chance at a better life. Dr. Gastman said his hope for Katie is that she continues to get better so that she can help others. According to the CDC, suicide is the third-leading cause of death for young people between the ages of 10 and 24, at about 4,600 per year.

“My hope for her is that her articulation improves, and she can get up there and tell that story,” Gastman said. “A fleeting moment can lead to something so devastating, not just for yourself, but for your family, and you’re seeing somebody who survived it.”

Katie now sees her life as a cautionary tale for preventing suicide. She hopes in the future she will be able to go into counseling or teaching.

“I really truly want to help everything in any possible way that I can,” she said. “Life is an amazing gift. Life’s beautiful. … Find someone to talk to, someone who will listen to you because life is a wonderful gift.”

This story will be featured in an upcoming “Nightline” report. Watch “Nightline” weekdays at 12:35 a.m. ET on ABC.

Source: Read Full Article