The decision on how to cover an expensive and controversial new Alzheimer’s drug could be settled by letting Medicare run its own trial to study payment and treatment implications.

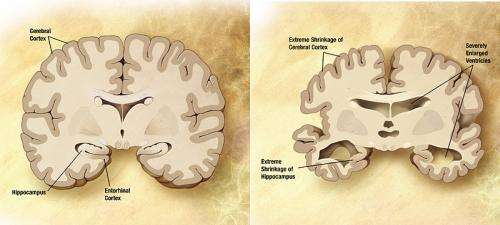

Aduhelm, from drugmakers Biogen and Eisai, won accelerated approval from the Food and Drug Administration earlier this month despite objections from the agency’s advisory committee. While clinical trials proved the drug significantly reduced amyloid beta plaques in the brain—which are associated with the disease—the drug failed to show evidence that it slowed progression of the disease itself.

The companies now have nine years to complete an additional clinical trial demonstrating that the drug can reduce the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, although revoking approval for a drug is rare.

Three members of the FDA advisory committee have resigned over Aduhelm’s approval, pointing to the lack of efficacy data and the high chance for dangerous side effects such as bleeding and swelling in the brain. Biogen’s $56,000 list price also sparked immediate backlash from patient advocates that included the Alzheimer’s Association, which pushed to get the drug across the finish line.

Focus has now shifted to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which needs to determine whether and how to cover an unproven drug at a cost capable of bankrupting the Medicare program. The drug has major implications as well for the Medicaid program, which has less authority to exclude coverage.

A few influential experts are now backing an idea to test both the cost and treatment implications through a payment pilot under the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. The office has sweeping authority to force providers to participate in experiments that waive provisions under federal law.

Peter Bach, director of Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Center for Health Policy & Outcomes, and Craig Garthwaite, director of health care at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, wrote an op-ed last week urging CMS to undertake a demonstration that would pay full price for the drug in some regions of the country, while paying nothing in other regions. The move would largely limit use of the drug to the covered areas, creating a control arm that would give CMS more data on whether the drug actually works.

“Evaluating whether payments are worthwhile is exactly the type of thing Medicare’s research center was created to do,” they wrote.

Bach chairs the Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee, or MEDCAC, which is sometimes tasked with assisting CMS when the agency sets national coverage standards for a particular product. Regional contractors make independent coverage decisions in the absence of a national coverage determination.

CMS has not said whether it plans to issue a national determination or whether one was requested by an outside group, but industry experts are confident that a national decision will be the ultimate outcome. If that’s the case, the agency might tap a handful of experts from the advisory committee to aid in deliberations.

The demo idea is also endorsed by Joseph Ross, the advisory committee’s vice chair and a Yale School of Medicine professor.

“My point of view is that if this product is going to be available on the market, then anyone who gets it should be entered into a clinical trial or some type of study for us to better understand the outcomes that are associated,” he told CQ Roll Call. “The challenge of it being just a study of patients who get this therapy is that to be able to observe changes in the progression of Alzheimer’s, any slowing of the decline in cognitive status would be really difficult to disentangle without a control arm.”

Melissa Garrido, a research associate professor at the Boston University School of Public Health and an advisory committee member, said she wasn’t sure CMS would determine that the drug is medically necessary. Some type of decision factoring in a requirement for additional evidence and data is possible, she said, although a demonstration would need to account for differentiating factors such as income and geographic disparities. Patients will receive the drug through monthly infusions and also need access to MRIs and PET scans to track progress and potential side effects.

“If a difference in outcomes is observed across the treatment and comparison group, there’s a chance it could be due to socioeconomic factors and not necessarily the drug itself,” she said.

It’s not guaranteed that Bach, Ross or Garrido would be on the advisory committee if CMS calls on the panel for help. The agency chooses a handful of experts from MEDCAC to analyze a product depending on the members’ expertise in a particular field. The drug’s detailed trial data is not yet public, and CMS could also overrule the committee’s recommendations like the FDA overruled its own advisory panel.

CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure has also not offered her thoughts on how the agency should approach Aduhelm’s coverage, although she acknowledged the severity of the disease. Alzheimer’s afflicts more than 6 million Americans, and is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States.

“We’re considering our options, and we’ll be looking very closely at the science moving forward,” she said on June 14.

A demo could bridge the gap between patients clamoring for access to a potential treatment and the need for a cost-conscious approach to gathering more data, but it could also further delay coverage. The national determination process could take around nine to 12 months, and the rule-making and implementation for a mandatory payment demonstration could take up to two years.

Mai Pham, founder of the Institute for Exceptional Care and CMMI’s former chief innovation officer, said CMS should consider a “multitiered” experiment if it decides to undertake a demonstration. CMS could condition coverage on clinical improvements made during the course of treatment, she said, or cap the length of treatment altogether.

Aduhelm was tested only in early-stage Alzheimer’s patients, but the FDA approved the drug for patients in all stages of the disease. The drug could also be limited to early-stage patients or to those participating in clinical trials.

Regardless, CMS will have to consider spillover effects from the drug across all of its programs, including in outcomes-based payment experiments like accountable care organizations. ACOs are groups of doctors and other providers whose payments are based on their ability to keep patients healthy and spending low.

“They’re graded relative to a target that is set for them by CMS,” Pham said. “That target is based on historical spend. Therefore, that target doesn’t know anything about the new drug.”

The political considerations are high. Pham said there is “no way” the lobbying forces behind the drug will allow the agency to block half the country from accessing the drug if they think they can stop it.

Source: Read Full Article