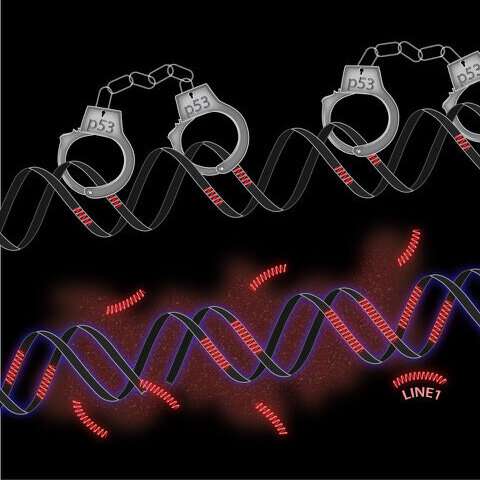

About half of all tumors have mutations of the gene p53, normally responsible for warding off cancer. Now, UT Southwestern scientists have discovered a new role for p53 in its fight against tumors: preventing retrotransposons, or “jumping genes,” from hopping around the human genome. In cells with missing or mutated p53, the team found, retrotransposons move and multiply more than usual. The finding could lead to new ways of detecting or treating cancers with p53 mutations.

“There’s been long-standing literature associating retrotransposons with cancer,” says John Abrams, Ph.D., professor of cell biology at UTSW and senior author of the study published recently in Genes & Development. “What this work does is deliver the first empirical link between p53 and retrotransposons in humans.”

The role of p53 as an anti-cancer, or tumor suppressor, gene has been well-established. It works by blocking cell growth, or inducing cellular suicide, when cells are under stress or dividing abnormally, as is the case in tumors. But researchers have long wondered whether the gene has another function. Even when the previously known targets of p53—genes involved in cell growth and death—are removed or mutated, p53 still protects cells from cancer, suggesting additional, unknown targets. Moreover, the gene is found throughout evolution, including in ancient single-celled organisms.

“These genes existed long before the need for blocking cancer,” Abrams says. “My lab has wondered what originally drove the evolution of p53 genes and whether that knowledge can help us target cancer.”

Retrotransposons are stretches of DNA that, after being transcribed into RNA, can insert themselves into new spots in the genome. These mobile genetic elements are considered beneficial to some degree—they can help genes evolve with new functions. However, they also have the potential to shuffle genomes and insert themselves into genes that are critical for cell health and growth, potentially contributing to cancer.

In 2016, Abrams and his colleagues discovered that retrotransposons were especially mobile when p53 was inactivated in cells of flies and fish. In the new work, they set out to study whether the same was true in human cells.

When the researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology to remove p53 from human cells, they found that the abundance of retrotransposons quickly increased. Cells derived from both cancers and normal lung tissue that were engineered to lack p53 had roughly four times the rate of retrotransposon movement than cells still containing p53.

Abrams’ team also introduced a synthetic, fluorescent-tagged retrotransposon to cells that let them follow the movement of the retrotransposon throughout the genome in real time. The results were similar to their first experiment; the retrotransposon was about four times more mobile, and therefore became more prevalent over time when cells lacked p53. The finding hints that one way in which p53 works to prevent cancer is by blocking retrotransposons from leading to other cancer-causing mutations.

“In the clinic, one could use this information to possibly detect or mitigate p53-driven cancers by quantifying or blocking retrotransposon activity,” says Abrams. A liquid biopsy, for instance, could be developed to detect an overabundance of retrotransposons that, theoretically, may precede cancers or be easier to detect than other cancer mutations.

Source: Read Full Article