With a storm in the forecast and snow already falling, my wife, Emily, arranges to leave early from her job at the hospital. I’m home cooking when she calls to report the roads are in rough shape and so are her tires. “I can’t believe I waited so long to replace them,” she says. “My stomach is in knots,” and mine tightens too. I want to stay on the phone, hoping my voice will soothe her, knowing it won’t.

Growing up, Em learned how to drive a tractor and a truck, and she knew how to change a tire before she got behind the wheel of a car. She is an excellent driver, which is good because I’m an excellent worrier.

I go downstairs to see an inch of snow already covering the parking lot. Without a shovel of my own, I drag my boot through the snow trying to find the diagonal yellow lines of our designated space. Then I make the mistake of calling back.

“I’ve never felt so unsafe behind the wheel,” she says, and explains that her tires have lost their grip. “I’m going really slowly.” I could have guessed that. I nicknamed her Sparky a long time ago because she moves with such careful determination. I walk to the front of our apartment building and settle in, like a dog on a porch waiting for its owner. For my wife, a drive is never just a drive, because she struggles with a set of illnesses that are as frustrating and mystifying as they are debilitating. Which means, of course, that so do I.

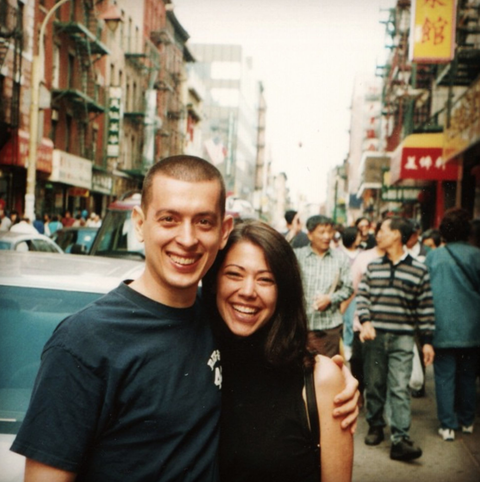

Em and I went to a suburban high school together an hour north of New York City, but we didn’t really meet until we were in our late 20s. It was a small school, so of course I knew who she was. She was one of the hot chicks—you don’t forget them—with full glossy lips, an upturned nose, and heavy-lidded stoner eyes. But she was only a pleasant, vague memory a decade later when we met with a group of mutual friends on Columbus Avenue one gray November afternoon. Em’s dark hair was slicked back into a bun and she wore a svelte black leather coat. When she shook my hand, she looked directly into my eyes and flashed that photogenic smile. The firmness of her grip came as a surprise from this five-foot sprite—“five and three quarters,” as she had it. Her laugh was genuine and easy, and I made her laugh right away.

She worked as a unit secretary at the nurse’s station of an emergency room and was going to nursing school. One thing for sure: Nothing about her suggested that she was sick.

Em was 22 and had just graduated from college when she developed Crohn’s, an incurable autoimmune disease. Five years and nine surgeries later, the illness consumed her life. At a time when most of her friends were getting their careers and families going, she became a professional patient, in and out of hospitals, preparing and recovering, forever going to specialists and surgeons who poked and prodded, cut her open and sewed her up again. The active disease was eliminated in an early operation when her large intestine was removed, but the scar tissue from subsequent surgeries presented its own complications.

“I’m not sick,” Em will say matter-of-factly. “I just need to take a lot of naps.”

Technically, that’s true. She’s in remission. But the aftereffects made it clear that she wasn’t what she had been—an athlete who hardly ever got a cold as a kid, did chores around her dad’s farm, and once spent a couple weeks in a tiny sailboat down in the Florida Keys on an Outward Bound trip. Now, after getting ready for work, she’ll lie back down in her scrubs for additional rest before she leaves.

There is no mercy at the dinner table. She has to eat often, noshing like a bird, but is restricted by what she can digest. Raw vegetables are out, but Em loves my salad dressing, so she’ll suck the dressing off a leaf of lettuce. Finding a restaurant can be exasperating to us both; I get frustrated at how many places we can’t go, and she feels like a drag and gets deflated, too. After eating, she’s careful to sit still while digesting because the scar tissue can lead to an “obstruction.” She’s endured a thousand small obstructions and half a dozen major ones that put her in the hospital, those dreaded visits always occurring in the middle of the night.

I thought I knew what I was getting into when we started dating. Em told me about the Crohn’s, but it wasn’t until the first time we made love that the reality set in. We were lying in bed in my apartment; Em stilled my hand as I started to unbutton her jeans, and prepared me for what was next.

I had never seen an ileostomy bag before and, now confronted with it, secured just above Em’s right hip, my curiosity masked my shock. I made sure not to look disgusted, and in fact, I wasn’t. I asked questions about how it worked and how often she changed it—you know, the usual foreplay. Then we moved on to the fun stuff, unfettered.

In our mid-30s, after we’d been together a few years, Em was diagnosed with chronic migraines and something called “convergence insufficiency,” which means her eyes don’t work in concert with each other, which you’d never guess because her eyes look perfectly normal. That’s because it’s actually a confounding neurological and spatial mishap—her vision is 20/20, but tracking anything on a page or a screen gives her a sinister headache. Em hasn’t been to a movie theater in more than a decade and has to limit use of her smartphone. She white-knuckles it through her shift at work, which, of course, involves looking at a computer screen—Em’s ailments knocked her out of nursing school after two years, but she continues to work part-time in the ER.

At home, I do the shopping and cooking; she does the laundry and accounting. I feel helpful when I can pick up any slack on chores, like preparing her lunch, to save her even a nominal amount of energy. She hates that she can’t do everything herself but isn’t too proud to appreciate the help. On the occasions when Em isn’t able to join me at dinner with friends or at family gatherings,

I field a barrage of well-meaning inquiries about her health. I’ve learned to gloss over them with “She’s just resting”—because how would getting into the complicated truth really help?

A good night’s sleep is the difference between a great day and a lousy one, so I tiptoe around the apartment until she’s awake, quieting my chirpy nature. I know she’s restored when she emerges from the bedroom and says, “Here I are,” which is what she said as a little girl the first time someone asked, “Where are you?”

That almost magical quiet that accompanies a snowstorm has settled on the city and I’m chucking snowballs at a stop sign when Em calls again. She isn’t close enough, but she’s making progress, and all I can think is: I can’t protect my wife.

Em can’t have children. She’s unable to conceive, and beyond that, doesn’t have the stamina to be a parent—which rules out adoption. It was a potential deal-breaker, and we dated five years before we got married, schlepping to couples therapy looking for answers. In time, she’ll feel better and change her mind, I thought, when actually it was me who had to accept that kids were not in our future.

You wish for love, but when it arrives, you never know how it will look. Kids or not, I love Em because I can be myself with her. She’s devoted, unwavering in her affection, forever cheerleading. I find her Post-its throughout the apartment—in the fridge or the medicine cabinet: “Morning handsome! I love my life with you!” We look at each other with curiosity and amusement because we have such different interests—she’s into neuroscience, sharks’ teeth, and photosynthesis; I’m into cooking, Buster Keaton, and the Yankees. (I used to think that kind of stuff—having the same taste—mattered. It doesn’t.)

Above all, I was attracted to her fighting spirit. There is something reassuring about being with someone who is not going to freak out in a crisis, and Em is unafraid when things get tough, which they always do. She doesn’t like being sick, of course, but understands the nature of living with sickness. Like fame or good looks, you’d best not make too much of these things. You learn how to deal.

Courtesy

I’ve had to learn it, too. Since I wasn’t going to be a dad, I doubled down on other pleasures and even tried to lose myself in caregiving. But when Em isn’t available sexually, I get frustrated, even take it personally. I curse my self-absorption. Here’s my wife, living in constant discomfort, and all I can think about is getting my rocks off. But the disappointment is there, and we brood, the tension mounting, before we fight. Early in our relationship, we were quicker to argue. I once punched the bedroom light socket in a fit of anger, but now our blowups are rare, and when I think I am going to do or say something I’ll regret, I excuse myself and take a walk around the neighborhood, to return only after I’ve cooled off.

Mostly, I handle my anger by denying it. Em asks, “What’s wrong?” And I say, “Nothing,” but she knows it’s something because she can sense it even if I can’t articulate it. I think I should be over being mad, so I ignore it and compensate by being overly nice, the hostility lacquered beneath all the courtesy and good intention. At times, I’ve stopped exercising, eaten too much food, and smoked too much weed. I haven’t chased women, but I’ll catch the hypnotic way a girl’s ponytail swings back and forth as she jogs along, and part of me can’t help but feel heartbroken for Em, who can’t simply throw on a pair of shorts and go for a run like she used to.

For years, I went to a men’s group run by a therapist I was seeing. In a room of five or six guys ranging from their 20s to their 60s—married, single, divorced—I’d talk about what was going on in my marriage. The group sympathized with my struggles, and there were times when the sound of another man’s voice expressing compassion made me feel less alone. The guys challenged me not to feel sorry for myself. I might be denied certain adventures in my marriage, but who has it all? Life is disappointing, they reminded me; how you handle it is what’s important—in my case, having trust that in the long run I will get what I need, if not everything I want.

The snow is wet and heavy when a plow finally trudges by, spritzing salt in its wake, like rice at a wedding. Tom Petty was right, the waiting is the hardest part. Waiting for her next appointment, for a new medicine to kick in, for her to get well. Waiting for her to digest so we can make love, waiting for her vision to clear so we can binge-watch Netflix like a normal couple. Waiting to stop waiting.

Em has been relentless in her pursuit of getting well. She visits neurologists and surgeons at prestigious hospitals and off-the-grid holistic practitioners. Em’s gone to talk therapy, practiced yoga and meditation, explored acupuncture, tapping, and craniosacral therapy—no modality is too obscure. With each doctor, she hits a dead end where they pass her along to the next specialist. Privately, she feels like a failure, as if being ill means that she’s weak.

Courtesy

“Do you think I will ever get better?” she asks, and I always say yes, because what else am I going to say? I need to believe it, too.

There are so many cars that look like hers that when I finally spot it, I’m not sure it isn’t a mirage. The car moves so slowly it seems to float, but it’s her. Of course it is—steady, unhurried, safe. Sparky, my beautiful tortoise. Here I Are.

She parks in the space I sort of cleared and looks drawn but relieved; it’s taken two hours to make the half-hour drive. Upstairs, Em changes into her pj’s and plops down on the couch. I put my right hand in the middle of her chest and she places her hands over mine. I used to think that because I was helpless to make her better I was also useless, but as she closes her eyes and presses my palm to her chest, taking in my warmth, I know that I am useful, like when I dice vegetables small enough for her to digest, or listen—really listen—to her without trying to solve or fix anything.

She’s hungry, so I heat up a small bowl of the polenta I cooked earlier. What a night. She tells me how she worked her meditation programs in the car but found it hard to concentrate. “I don’t even want to tell you what was going through my mind,” she says.

I tell her she doesn’t want to know what was going through mine.

We agree to leave it at that.

Navigating Sickness and Health

Of the roughly 44 million unpaid caregivers in the U. S., 40 percent are men. And when it’s your partner that you’re caring for, you’re not just dealing with an illness. You’re dealing with a changed relationship. To help steady your course:

Give the rock a rest.

“Male caregivers, in general, have the tendency to play tough guy and not allow themselves to experience any feelings,” says Barry Jacobs, Psy.D., a clinical psychologist who’s a national spokesperson on family caregiving for the American Heart Association. That breeds a conspiracy of silence that shuts out your partner and doesn’t give honest conversations—the stuff healthy relationships are built on—a chance. “Illness doesn’t kill a relationship; lack of intimacy does. It’s hard to feel warm and fuzzy about a warrior,” he says. (Which also explains why people’s sex lives evaporate.)

Team up.

You’ve got to find a way to bring up what you’re feeling, even if it’s negative. One way to start is to define the illness as a couple or family issue—“us against the disease,” says C. Grace Whiting, CEO of the National Alliance for Caregiving, a research and

advocacy group. Then together you can acknowledge what has been lost and the

sadness around that.

Consider “That must be hard” to be an answer.

“This is a generalization, but men tend to want to fix things,” Whiting says. “Women often just want someone to listen to them.” So “I’m sorry you’re going through that; tell me more about it” is a perfectly reasonable response when your partner starts talking about what’s wrong.

Courtesy

Build a new fire.

Limping along and trying to pretend nothing has changed becomes an exhausting chore of fanning the embers of what used to be. Instead, find ways to construct your new reality; look for new things you can do together that are different but still meaningful. They can be daily rituals or special events, but shouldn’t be about the illness or caregiving—you already have enough of those.

Collaborate.

“Out of all best intentions, the well partner often takes on more than they should, making the ill spouse feel disempowered and diminished,” Jacobs says. “That affects the level of affection between you.” The relationship may never again be as egalitarian as it was, but it’s important to feel like there’s effort on both sides (even as simple as Em’s Post-its around the house). Figure out how each of you will contribute.

Not going well? Talk to people who’ve been there: Try the Well Spouse Association (wellspouse.org) or Hidden Heroes, designed for military caregivers (hiddenheroes.org); both have advice and support communities for navigating the new normal.

Source: Read Full Article